In conversation with Hannah Regel

“The book is so much about doubt, self-identity, and how you perceive yourself…”

- Hannah Regel

Hannah Regel

Poet and novelist Hannah Regel’s debut novel, The Last Sane Woman, is a compelling exploration of the emotional lives of two aspiring artists living at different times, yet connected by the discovery of a box of letters in a forgotten feminist archive. It is an assured study of friendship, success, envy, and what it means to be an artist.

FLO contributor Ellen Hodgetts sat down with Hannah to find out more about her creative process and some of the influences behind the novel.

This is your debut novel after writing two poetry collections (When I was Alive and Oliver Reed).How did this change the way you approached the work?

It happened quite naturally. Initially it was more poetic and experimental in its form, I worked on it very slowly and it just grew and grew. As I spent more time on it, it started to become more novelistic in terms of the character development and plot but that was almost an accident. It started off as unconnected fragments and it slowly got knitted together.

What led you to focus on ceramics as the main form of art in the novel?

Aside from how rich ceramics and pottery can be metaphorically – clay comes from the earth and it has to undergo this process with the hands and then it’s fired to become permanent – if you’re thinking about history and archives as well it lends itself quite happily to that. The book is so much about doubt, self-identity, and how you perceive yourself, and I think you’d be hard pressed to find another art form whose status is so contested in terms of whether it’s fine art or functional.

You also have a background in art. How did your own experiences feed into the characters and world you created?

I went to art school, so I’ve made pots, but I was already writing at the same time. I never tried to make a career as an artist. I have worked with clay in the past, but I think that to an extent all art forms have the same set of struggles.

When I was describing some of the emotions Donna goes through it’s completely the same with writing. You have to sit there and generate it from inside of you, it doesn’t come from anywhere else – you have to be bizarrely overconfident and at the same time it’s very humbling.

The perspective shifts between Nicola, Donna and Susan and becomes more fragmented throughout the novel. I’ve seen it compared to Virginia Woolf - were there any particular literary influences that shaped The Last Sane Woman?

I’m thrilled with the Virginia Wolf comparison, I love her a lot. When I was writing The Last Sane Woman, I read a book called Meridian by Alice Walker- it doesn’t seem to be very well known but it’s brilliant, I can’t understand how more people haven’t read it!

It’s about the civil rights movement and it tracks one woman’s life from childhood to death, but it toes the line of incorporating the world of dreams and fantasy into reality really well. Anyone who does that – so Denis Johnson for example – is a big influence. It’s the same in Virginia Woolf’s writing, the world of dreams and fantasies blends into realities.

One difference between Nicola and Donna is that Nicola exists in the online world too. How do you think social media has impacted artists and creators?

I suppose something similar will always have existed in some kind of warped capacity, even before the social media age. But now it feels like you’re on show a bit more, or there’s a pressure to opt into the cult of the personality that runs alongside it. I’m quite a private person, I find it quite frightening – but I also feel myself compelled to do it.

You referred to Nicola as experiencing a ‘crisis of desire’ – could you explain a bit more about what you mean by this and how desire fits into the narrative of the book?

When we meet Nicola at the start of the novel, she doesn’t know what it is she wants. She has an idea of it but she’s so easily influenced by outside forces. Her desires and impulses are in crisis. She talks about wanting to be an artist, but doesn’t really seem to be that invested it in and doesn’t do it either. Then as the book goes along she ends up having this sort of Katy Hessel idea of herself that is also never really realised. She’s quite impressionable, and this element of her personality drives the narrative of the novel – otherwise the archive wouldn’t have such an influence and hold on her.

The Los Angeles Review of Books described the novel as ‘simultaneously comforting and uncanny’. What were you trying to achieve with the uncanny elements?

On some level the uncanniness is sort of a trick – it builds from the connection that Nicola feels to Donna and to the letters in the archive. There are some similarities, they’re from the same place and they tentatively do the same thing, but that’s where it ends. They’re not actually that similar at all and their lives take completely different trajectories.

It’s a delusion and a construct in Nicola’s head, but I wanted the reader to be complicit with her and the impulses she feels towards Donna. She has this impulse to see the body and know how it ends, to pull the curtain down. I really wanted the reader – maybe against their better judgment – to want that too. The uncanniness is a smokescreen to get you on Nicola’s side, and that’s what gives the narrative its forward motion.

Can you tell me a bit more about the friendships in the novel and how you developed these characters?

For a very long time the whole book was just the dynamic between Donna and Nicola and Susan wasn’t really in it at all. Everyone I showed it to or got any feedback from actually said that it was a bit boring! Someone suggested that it needed a third voice to triangulate it and shift the perspective a bit, so then Susan came in. Once I let that happen, it seemed to fall into place a lot more easily. Susan’s voice opened it up, and there was so much room for bringing even more people in. So you have Marcus and Leonie and these people that encounter both Donna and Susan at various different points and bring up feelings of inadequacy or jealousy.

The friendships you have with people you’ve known since you were very young can often have an interesting dynamic. With Donna and Susan they are almost trapped, they can’t let the other be different from how they view them – you’re the creative one, you’re the motherly one. They box each other into these categories and don’t allow the other to have a fully rounded personalities in case it destabilises the dynamic. There’s something quite violent about it. They can’t let each other change and it can get quite constrictive. Susan rolls her eyes a lot and doesn’t take Donna seriously. They’re not very nice to each other a lot of the time!

What else are you working on at the moment and what would you like do next?

I’m trying to write another novel. My dad is Bengali, so it’s sort of about my family, another historical book, but I’m going very slowly at the moment! I also want to get back into writing poems as I got out of the habit and I miss it.

Hannah Regel’s debut novel, The Last Sane Woman, is out now.

Debut London Literature will present the new works of Hannah Regel, Varaidzo, Kaliane Bradley and Tom Lamont, chaired by Barry Pierce at the Southbank Centre’s London Literature Festival on 23 October. Tickets from £12. southbankcentre.co.uk.

Interview by Ellen Hodgetts

Judith Clark is a curator and fashion exhibition-maker, and currently Professor of Fashion and Museology at the University of the Arts London. She lectures on the MA Fashion Curation and is a founding Director of the Centre for Fashion Curation. From 1997 to 2002, she ran London’s first experimental fashion gallery in Notting Hill…

Lindokuhle Sobekwa is a South African photographer from Katlehong, Johannesburg. Since his first exhibition in 2013, his work on social issues and personal histories—like his photo essay Nyaope—has gained international recognition. A member of Magnum Photos, Sobekwa was recently awarded the 2025 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize for his project I carry Her Photo with Me…

Sol Bailey Barker is a multidisciplinary artist whose work explores the connections between ecology, mythology, and speculative futures. Through sculpture, sound, and installations, they blend ancient knowledge with emerging technologies to examine humanity’s relationship with the natural world…

Hanna Salomonsson is a London based Swedish ceramic artist. Following a career in landscape architecture, she re-trained in ceramics in 2018. She also holds a BA in Art History, and this combined with her landscape grounding provides a unique vantage point for her ceramic practice…

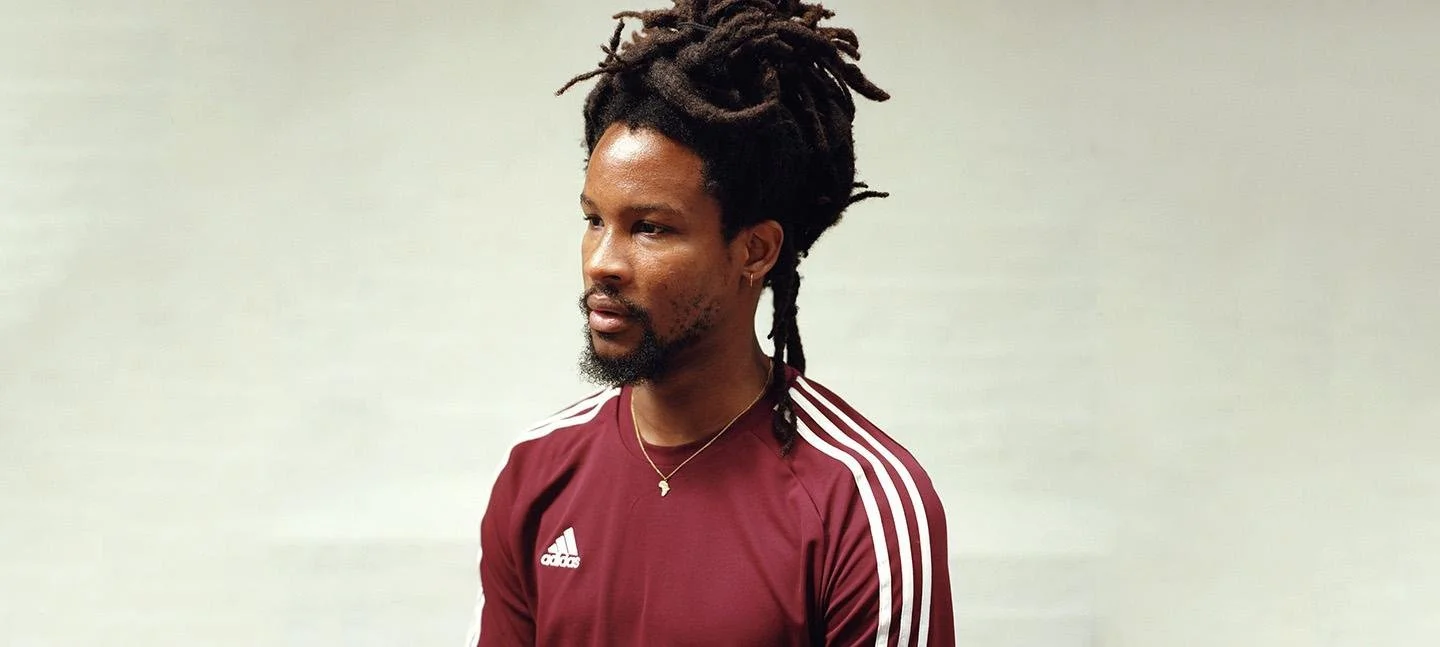

Lewis Walker is a London-born queer, non-binary movement artist. A former Great Britain gymnast and Acrobatic Gymnastics World Champion, they trained from age 6 to 21 before earning a degree in Contemporary Dance. Their work spans theatre, film, fashion, music, and the commercial sector. Walker continues to choreograph gymnastics competition routines for the Great Britain, Italian and French national teams…

Daniel is a curator-producer dedicated to the social impact of the arts and cross-sector collaboration. He is currently Creative Director & Chief Executive of Old Diorama Arts Centre (ODAC) in Euston, where he has strengthened the centre’s community connections amidst urban transformation…

Peter Bellerby is the founder of Bellerby & Co. Globemakers, a company renowned for its exquisite hand-crafted globes. Established in 2010, the company specialises in meticulously designed pieces that showcase exceptional craftsmanship, positioning Bellerby & Co. as a leader in the globe-making industry…

Gabriele Beveridge is known for her sculptural and conceptual practice that combines materials as diverse as hand-blown glass, photo chemicals, and found images…

Robyn Orlin is a South African dancer and choreographer born in Johannesburg. Nicknamed in South Africa "a permanent irritation", she is well known for reflecting the difficult and complex realities in her country. Robyn integrates different media into her work (text, video, plastic arts) to she investigates a certain theatrical reality which has enabled her to find her unique choreographic vocabulary…

Katrina Palmer, an artist known for exploring materiality, absence, and dislocation, recently spoke to us following her year-long residency at the National Gallery about her exhibition The Touch Report…

Enej Gala is an artist who splits his time primarily between London and his hometown of Nova Gorica, Slovenia. A graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice and the Royal Academy Schools (2023), Gala first gained our attention with Neighbour’s Harvest, an installation that cleverly combined puppetry and conceptual art…

David Ottone is a Founding Member of Award-winning Spanish theatre company Yllana and has been the Artistic Director of the company since 1991. David has created and directed many theatrical productions which have been seen by more than two million spectators across 44 countries…

Darren Appiagyei is a London-based woodturner whose practice embraces the intrinsic beauty of wood, including its knots, cracks, bark, and grain. Highly inspired by Ghanaian wood carving, Darren explores raw textures and new woods in his work…

Huimin Zhang is an artist specialising in 22K gold, known for her innovative craftsmanship. She combines various cultural techniques, including filigree, engraving, and European gold and silver thread embroidery, to create unique works…

Akinola Davies Jr. is a BAFTA-nominated British-Nigerian filmmaker, artist, and storyteller whose work explores identity, community, and cultural heritage. Straddling both West Africa and the UK, his films examine the impact of colonial history while championing indigenous narratives. As part of the global diaspora, he seeks to highlight the often overlooked stories of Black life across these two worlds.

Hannah Drakeford is a London-based interior designer known for her bold and colourful interiors. She transitioned from a 21-year retail design career to interior design, and has gained popularity on social media where she now shares creative upcycling tutorials and encourages individuality in home decor…

Shula Carter is an East London-based creative with a background in contemporary, ballet, and modern dance. She trained at the Vestry School of Dance and later at LMA London, where she developed skills in commercial, hip hop, and tap dance, alongside stage and screen performance…

Dian Joy is a British-Nigerian interdisciplinary artist whose work delves into the intersections of identity, digital culture, and the fluid boundaries between truth and fiction. Her practice is rooted in examining how narratives evolve and shape perceptions, particularly in the digital age.

Dian Joy is a British-Nigerian interdisciplinary artist whose work delves into the intersections of identity, digital culture, and the fluid boundaries between truth and fiction. Her practice is rooted in examining how narratives evolve and shape perceptions, particularly in the digital age.

John-Paul Pryor is a prominent figure in London’s creative scene, known for his work as an arts writer, creative director, editor, and songwriter for the acclaimed art-rock band The Sirens of Titan…

Jim Murray is an actor, director, conservationist and artist known for Masters of Air (2024) and The Crown (2016). Murray first came to prominence as an artist in 2023 with his acclaimed inaugural exhibition In Flow, where his dynamic abstract paintings were hung in conversation with John Constable’s The Dark Sid…

Anthony Daley is an abstract expressionist painter known for his vibrant, large-scale works that explore beauty through intense colour and light. His art bridges the past and present, drawing inspiration from the Old Masters as well as diverse sources like literature, science, poetry, and nature.

Rachel Kneebone’s work explores the relationship between the body and states of being such as movement, stasis, and renewal. Through her porcelain sculptures, she examines transformation and metamorphosis, reflecting on what it means to inhabit the body and be alive…

Saff Williams is the Curatorial Director at Brookfield Properties, bringing over fifteen years of experience in the arts sector…

Sam Borkson and Arturo Sandoval III, the acclaimed LA-based artists behind the renowned collective "FriendsWithYou," are the creative minds behind "Little Cloud World," now on display in Covent Garden. During their recent visit to London, we had the privilege of speaking with them about their creative process and the inspiration behind this captivating project.

Kinnari Saraiya is a London-based Indian artist, curator, and researcher whose work focuses on trans-altern and post-humanist ideas from the Global South. She is currently a curator at Somerset House and has held positions at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Frieze Art Fair, and Bowes Museum....

Fusing her Asian roots with a fascination for African pattern work and her deep passion for architectural geometry, Halima’s work is intense yet playful, structured yet creative; substantial yet dynamic and invariably compelling in its originality.

Matilda Liu is an independent curator and collector based in London, with a collection focusing on Chinese contemporary art in conversation with international emerging artists. Having curated exhibitions for various contemporary art galleries and organisations, she is now launching her own curatorial initiative, Meeting Point Projects.

EKLEIDO, a choreographic duo formed by Hannah Ekholm and Faye Stoeser, choreograph performances for live shows and film.

Lydia Smith is one to watch. Currently on show in three different places across London, her work can be seen in a solo exhibition in the City, a group show in a chapel in Chelsea and through a new series of monumental sculptures installed outdoors across sprawling parkland…

Following the success of its landmark tenth anniversary, Photo London is poised to embark on a transformative new chapter in 2026 by relocating to the historic National Hall at Olympia, Kensington. ..

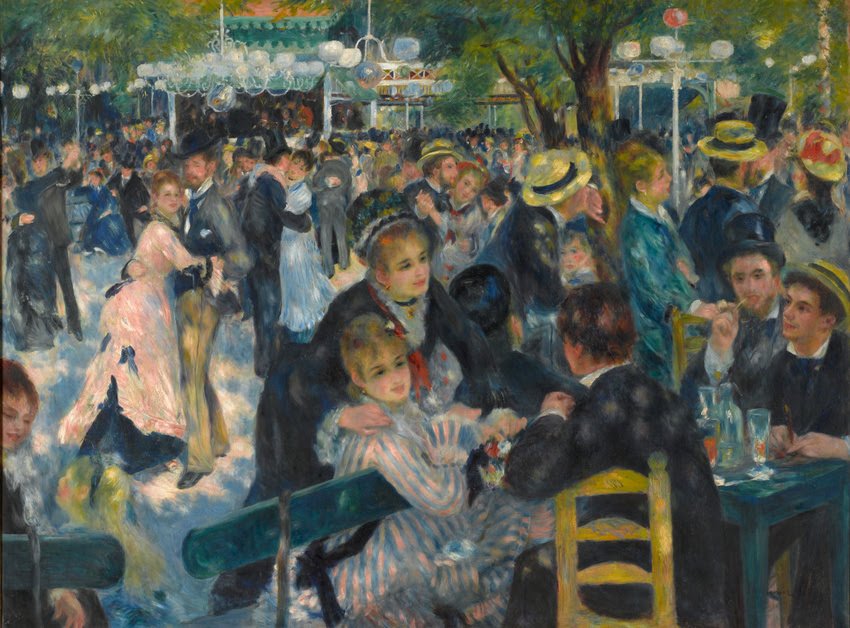

In autumn 2026, the National Gallery will open Renoir and Love, a landmark exhibition exploring the romantic and social dimensions of Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s art. With over 50 masterworks on display, this will be the most significant UK exhibition of the French Impressionist’s work in two decades…

In 2026, the V&A Museum will present Schiaparelli: Fashion Becomes Art, the first major exhibition in the UK focused on Italian designer Elsa Schiaparelli. Opening at the Sainsbury Gallery in March, the exhibition will trace the development of the House of Schiaparelli from the 1920s to its recent revival under current creative director Daniel Roseberry….

La Terrasse by GREY GOOSE is now open at Rosewood London, inviting guests into an elegant summer escape in the heart of the city. Set within the hotel’s grand Belle Époque style courtyard, this alfresco haven is inspired by the charm of the French Riviera…

This week in London (7–13 July 2025) offers a spectacular mix of entertainment, from pop-up concerts and underground club nights to festivals, art, theatre, opera, exhibitions, outdoor cinema, and community-focused events…

Vienna, the Austrian capital, is home to a wealth of incredible art institutions, making it an essential destination for art lovers this summer 2025. With its close proximity to London, the city offers a captivating mix of exhibitions ranging from historic institutions like the Albertina and Belvedere museums, showcasing classical masters, to contemporary spaces including Kunsthalle Wien, Belvedere 21…

Autumn is always a busy time for art in London, with Frieze Week in October drawing international attention. But beyond the fairs, the city’s museums and galleries are offering a strong line-up of exhibitions worth seeing. From the V&A’s exploration of Marie Antoinette Styleto Tate Modern’s major survey of Nigerian Modernism, there is much to engage with. Dirty Looks at the Barbican…

With shows ranging from historical military art to queer talismans, pop protest, and the power of drawing, here is our guide to the art exhibitions to see in London in July 2025…

Edward Burra described painting as a ‘sort of drug’, a tonic to the rheumatoid arthritis that plagued his daily existence. Under its influence, he became one of the great observers of the twentieth century, creating vivid and surreal scenes that captured a rapidly changing society. The latest exhibition of Burra’s work at the Tate Britain…

This week, the Hayward Gallery has opened the touring exhibition of Yoshitomo Nara, expanding on the blockbuster shows previously held at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and the Museum Frieder Burda in Baden-Baden. The exhibition includes both early and more recent sculptures, with some works created as recently as last year…

What’s on in London this week (16–22 June): A vibrant round-up of London’s best art, theatre, music, food, and free events—plus the return of the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition and a seafood hotspot opening in Shoreditch…

This summer, Bozar presents a compelling trio of exhibitions that pose urgent questions about who we are, how we see one another, and what we carry — both within and across cultures. From When We See Us, a sweeping survey of Black figuration across the last century, to Berlinde De Bruyckere’s haunting sculptural works in Khorós, and Familiar Strangers, which reflects on shifting identities in Eastern Europe…

July is one of the best times to be in London, with a wide range of events taking place across the city. Catch world-class tennis at Wimbledon, dance into the night at Wireless Festival or BST Hyde Park, and enjoy open-air cinema with skyline views…

This week in London will see the return of the HSBC Women’s Tennis Championships at Queen’s Club, the opening of Yoshitomo Nara at the Hayward Gallery, Eel Pie Island Open Studios, and LIDO Festival in Victoria Park…

A guide to art exhibitions to see in Brussels this summer, from Baucher and Feron’s Art Deco interiors to When We See Us, a landmark show on Black figurative painting curated by the late Koyo Kouoh, and Looking Through Objects, a compelling survey of contemporary Polish women designers…

London is set to serve up an extraordinary tennis season in 2025, offering fans an exciting mix of elite competitions across some of the city’s most iconic venues. From the historic grass courts of The Queen’s Club and the All England Lawn Tennis Club to the exclusive courts of the Hurlingham Club, tennis enthusiasts can look forward to a thrilling lineup of…

What’s on in London this week? From the London Design Biennale and Serpentine Pavilion to WOW!house at Chelsea Harbour and London Open Gardens — discover the city’s top exhibitions, performances, and cultural highlights…

Meltdown Festival 2025 – Curated by Little Simz · London Design Biennale 2025 · Royal Academy of Arts – Summer Exhibition 2025 · London Festival of Architecture 2025 · London Open Gardens 2025 · Serpentine Pavilion 2025 – Marina Tabassum: A Capsule in Time · London Gallery Weekend 2025 · Camberwell Arts Festival 2025 – ‘Free For All’ · ICA – Connecting Thin Black Lines: 1985–2025 · Saturday Sketch Club – Royal Academy of Arts · Botis Seva / Far From The Norm – Until We Sleep · London Road – National Theatre Revival · Eel Pie Island Open Studios · Wandsworth Arts Fringe…

Your essential guide to what to see and do across London during the London Festival of Architecture 2025 — a citywide celebration of architecture, ideas, and community, featuring everything from late-night studio openings and thought-provoking talks to exhibitions, documentaries, and large-scale installations…

This summer, the Barbican Centre in London presents Frequencies: the sounds that shape us (22 May – 31 August), a dynamic and multi-disciplinary season dedicated to exploring the transformative power of sound and sonic experience. Here are 10 unmissable events within the Frequencies season…

From Clerkenwell Design Week, Wide Awake Festival to the Chelsea Flower Show, London offers a rich mix of theatre, exhibitions, live music, and cultural events from 19–25 May. Discover standout performances, thought-provoking art, and unique experiences across the city…

Discover a range of exhibitions opening in London this June, from the Kiefer / Van Gogh show at the Royal Academy to Dan Guthrie at Chisenhale. Explore bold solo displays, landmark retrospectives, and events like the London Design Biennale at Somerset House and London Open Live at Whitechapel Gallery…

Experience London at its most vibrant during Chelsea Flower Show 2025, with a city-wide celebration of flowers, art, and culture. From dazzling floral displays in Chelsea, Belgravia, and Brompton, to themed teas, flower-covered taxis, and world-class exhibitions, discover the best events and serene garden escapes blooming across the capital…

Discover the best things to do in London from 12–18 May 2025, from exploring global design at London Craft Week to seeing Jane Eyre brought to life by Northern Ballet, making your own bouquet at Sketch with Wild at Heart, or experiencing the striking Gilbert & George exhibition DEATH HOPE LIFE FEAR… in East London…

Discover must-see art exhibitions in Margate this summer, from powerful shows at Turner Contemporary, Carl Freedman Gallery, Quench Gallery, and Liminal Gallery to public commissions by artists like Tracey Emin, Antony Gormley, and Yinka Ilori….

Discover the best UK festivals to visit this summer with our guide — from the legendary Reading & Leeds Festival and the elegant opera of Glyndebourne, to the music and wellness haven of Wilderness and Glasgow’s very own TRNSMT…

Discover our guide to what’s on in London this week (5–11 May), from Tate Modern’s 25th Birthday Weekender and Peckham Fringe to new exhibitions, open-air theatre, live music, film, and more...