In conversation with Rachel Mars

“So historically, if you are coming to a Rachel Mars show, I am going to be chatting and it's going to be interesting, funny, well-constructed, and be about something political that also has a personal aspect to it. FORGE, I don't say a damn thing. So, it's different.”

- Rachel Mars

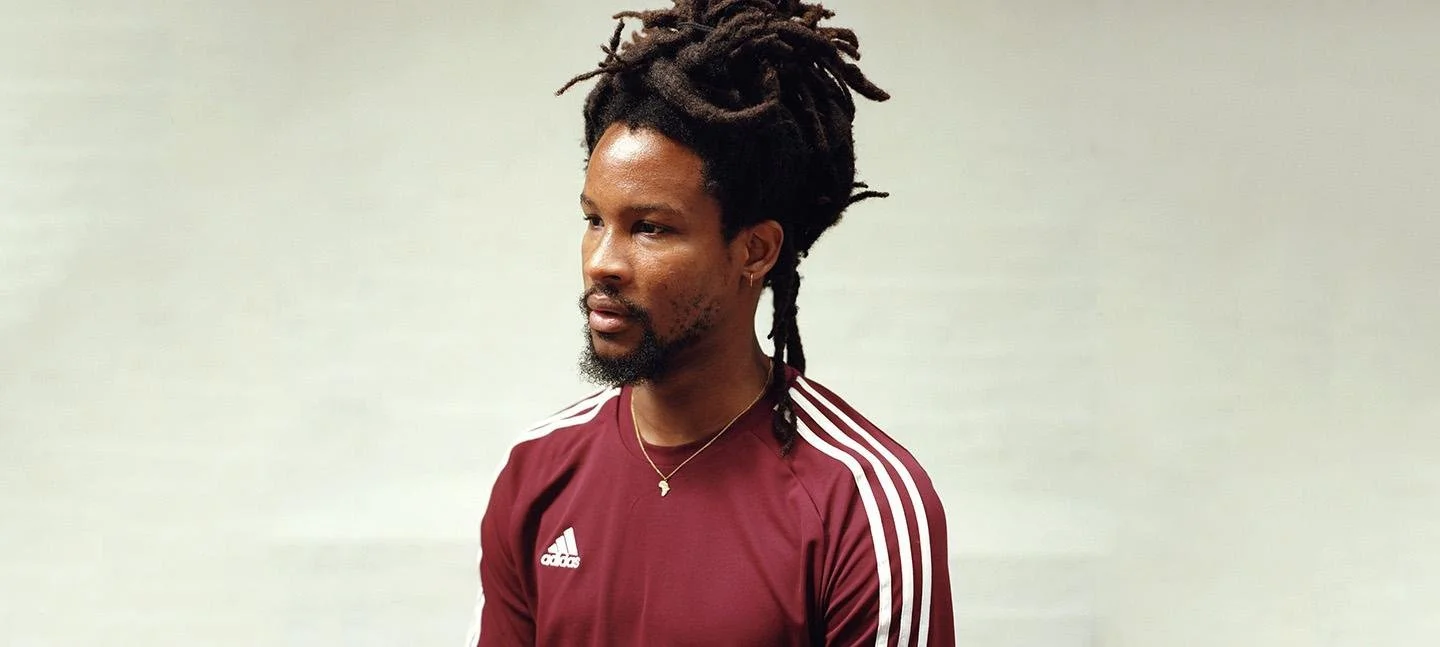

Image: Rachel Mars. Image credit Benkin photography

Rachel Mars is a performance artist, with a background in theatre, live art, and comedy. Her work often explores the intersections of the personal and the political, navigating Jewish identities, female bodies, and queerness. She was a fellow at the Birkbeck Centre for Contemporary Theatre in London, and now teaches artistic workshops in the UK, Canada, and in the US. Recent projects include: Your Sexts Are Shit: Older Better Letters, Our Carnal Hearts, and Gaping Hole.

Forthcoming at the Barbican from 17 - 20 May, Rachel Mars will be performing FORGE. FORGE investigates themes surrounding memorials and replicas in the monumentation of traumatic histories and events. When the ‘welcome’ gate was stolen from the Dachau concentration camp in 2014, a local blacksmith created a replica of the sign. In FORGE, Rachel works for four days to weld a replica of the stolen sign. FORGE speaks to the idea of memorial, asking questions of “decay, hallowing, closure and our responsibility to the present.”

Rachel developed the show during her residency as part of the Barbican’s Open Lab creative development programme. Please read more about the show here or on the Barbican website.

How did your journey into art begin? What was that trajectory like?

I was super lucky to be taken to the theatre as a kid. So I think it was a combo of having parents that took me to see stuff and coming from, in the home, a Jewish storytelling tradition. Not that we were telling stories, but storytelling was highly prized, being good at telling stories was highly prized, and telling gags was highly prized. So I think it was this combo of being practised from within the home at storytelling and then being lucky enough to be taken to see stuff outside the home. Also, this was the day when there was still funding for kids to go to the theatre in schools. So I also got taken to the theatre as a kid, not [just] by my parents. It was that sort of thing, really.

Then I ended up going to university to do English and Theatre together, in a course that had quite a lot of freedom to make your own work. It wasn't like 'Now we do Shakespeare,' 'Now we do Chekhov.' It was quite alternative in the way that they introduced you to theatre stuff. So it was that sort of combo. After university, I was working at the same time as trying to make my own stuff in the evenings. So from there onwards... it’s been ages.

How would you describe your artistic style and the recognizable characteristics of your work in the physical sense?

FORGE looks nothing like anything I have ever made before, so that's a bit of a spanner in the works. Historically, my work is collaborative. It's historically been stuff that I have written in a devised manner, or [that] I have written and is being worked on in the room. So it's not 'a play.' Although that too is changing... everything's changing. [My work] is characterised [by] quite a strong intellectual, theoretical background. And then, in the moment, pretty accessible, pretty funny, pretty wordy. That sort of thing.

But FORGE is nothing like that. I mean... it is. It's intellectual. But FORGE... I don't say anything in FORGE. So historically, if you are coming to a Rachel Mars show, I am going to be chatting and it's going to be interesting, funny, well-constructed, and be about something political that also has a personal aspect to it. FORGE, I don't say a damn thing. So, it's different.

What catalysed that change for you? What made you want to explore something new?

It was a mixture of the pandemic meaning that, at that time, the way I was headed with FORGE wasn't on offer. And actually, it revealed the truth of what I needed the show to be, which was one action. I have never made a 'one-action' show before. But, I was like 'Oh actually, what this requires is this body making this gate and being observed doing it. That's actually — in its simplest form — what it needs to be.'

There's an exhibition when you come in and you hit it in a take-home pamphlet book when you leave. So the language is there, I am just not speaking it. It's the form and content coming together really. It's a weight off for me as well... I can't do 'The Holocaust Show.' I mean, it's more complicated than that, but I think the visuals do a lot of work in it for me.

What sort of messages and themes do you try to communicate in your work? And, how has that evolved over the years?

Looking back, it's always both a political question combined with something that's going on personally at the same time. So the show I made called Our Carnal Hearts was about envy and competition. It was asking questions of the political use of envy to pit us against each other for capitalism to continue. So that was the big political question. But it was also looking at what it is to be an artist [when] you're pitted against your fellow artist, all the time. And then, put in a world of scarcity and told that you can't be honest when your mate gets something you don't and you're pissed off about it because that's taboo. And actually, wouldn't it be a lot nicer if we were just able to be like, 'I’m fucking pissed off that you got that. I applied and I didn't get that,' and then you can move on through it?

So it's this combo of something that's affecting me and people personally as [well as] a political question. We did a show called ROLLER, on the one hand about female aggression and roller derby. But that came just at the beginning of the Harvey Weinstein/Me Too stuff. So this action keeps happening (she motioned her hands in a sort of weighing to signal the interaction). It's this big political question combined with questions of the female body really and how to live in it. It's always about social interaction and how we are with each other.

You talk a lot about queerness and being Jewish. Can you speak a little about how those facets of your identity play into your life as an artist? Both sort of in the physical representation of the art and any other way you want to take it?

It's interesting. I think we are working in more siloed [ways]. I think in the past 15 years I think we have moved more into 'I am a bleep-bleep artist' as a way of describing. Which I understand and appreciate in some ways. I think the Jewishness and the queerness sit together in my perspective of being seemingly white-presenting but in a British culture where I both pass and don't pass depending on who is looking at me and depending on how I am feeling in a situation. So it's a particular kind of insider/outside experience being a white Jew in Britain.

Queerness is another just-slightly-outside the lens of a normative experience. It gives me that classic artist position of looking from an outside position into something and [offers] a bit of space in going, 'These are the forces that are operating on me,' 'These are the forces that are operating on people that are seemingly normative in other ways and because of that they don't realise it’s operating on them.' So that kind of position is where I am operating from and the space it gives and the discomfort.

How do you feel like that's influenced the art that you make, especially the discomfort?

With the really barbed humour that I use. It’s that kind of 'jester' world of skewing something. Having had the distance from a very, very mainstream experience: to reflect on something and then being able to present that back and be like 'this is the world we are operating in' but with barbed humour. I think the Jewishness in my work comes out in the way that I use humour and the tricky places that you can get into with comedy.

Image: Rachel Mars, FORGE. Image credit: JMA Photography

With FORGE being at the Barbican this month, can you tell us a little about how the project came together and what it has meant to you?

Yeah, it's been a really long process: A. just because it has been, and B. because of the pandemic. We had just put the lights up for a tech rehearsal in 2019 — not at the Barbican, it was for the Barbican, but we were in a different theatre. So we had literally put all of the lights up and then were like 'yeah... it's not gonna happen' so we took them down. Then, it was the first thing I returned to after the pandemic. So it's sort of bookended that. After the pandemic… we are still in it. But after the banning of theatre.

So it's been brewing for a super long time since I found out about this gate being stolen in 2014 from Dachau. As these sites where terrible things happen decay, what decisions are we going to make about keeping them pristine or not? And, what it is to have replica or a replica object amongst these authentic objects? I've always been interested in nation-states and intervention in memorial. By having a national monument to something, what that does to the complex narratives of [the event]? The political stuff there.

I'm a third-generation Jewish person whose Grandparents escaped in '39 and made it to Britain. So that's the personal scene, like what do you do with that inheritance? And how does it play out in the present? And how are you always sitting in the present and facing the attempt to face the future when you've got that in your past? It's constantly pulling you to turn around and be in the past. So it's those kinds of things.

Then, [it’s] this idea about bodies — or Jewish female bodies — being not particularly practical which is a stereotype that lives as Jews as bookish and intellectual. So going 'No I am going to build this thing myself. I am going to build it. And, I am going to be practical. And, I am going to learn practical welding. And, I am going to do this metalwork myself.' So, [it was] all of these starting points to make a show that's really asking questions about inheritance but also about memorial.

What sort of experience of that do you envision visitors having? What are the takeaways you want them to go away with?

It's a really particular experience because you hit essentially a very small art installation exhibition. Then you have to put on a welding mask. So your perception is changed immediately because you can only see through a letter box essentially that blacks out every time you look at it. When welding happens, it blacks out. Your perception is physically changed by being in the exhibition.

I work with a sound artist called Dinah Mullen and so there's this constantly changing live soundscape that you're experiencing that will be different for everything person. We don't just press play and we're off for five days. You spend time there and then you leave. It's the most abstractive thing I have ever done.

The anxieties as a theatre person are like, ‘It's not enough, we haven't told them exactly [what to think].’ Like I can't control it. We hope that we have done the control in the architecture of [the exhibit] and what we have created. But once you're in, if I feel the audience is having a boring time — which I don't think they are — I can't just flip up my welding mask and tell some gags and check in that everyone's alright. Historically I can feel, on stage, when I need to speed something up or move on. That's not on offer to me this time. So it's a very different experience for me because I just need to do the work and trust that the audience is having the experience that they are having.

So that kind of question of 'what do I hope?' People have had really broad responses to it in Leeds, the first time around. I think it's the most open — even though in some ways the subject is so specific. It’s a really open offer for people to just come and be in this environment knowing what they know [from what] we've told them in the exhibition about why I'm doing it and why they're here.

I hope people go away thinking about memorial culture. I hope they go away thinking about difficult histories. I hope they go away thinking about Britain and how it's behaving towards people that need to be here and are not being allowed. Yeah, that sort of world.

Did you draw on any inspiration from other artists? Are there any past or present artists that played into this work that have inspired you?

I'm trying to think. It's more people. It was female welders that I had met and the way that they were working, and the kind of elegance of that. It was looking at memorial architects and the way that they are thinking about what they've got to memorialize and how that's playing out in the buildings that they are creating.

On the whole, I have made something that I, myself, would be incredibly impatient with. I am quite impatient when it comes to durational work. I'm like ‘Come on.... how long've I got to be here? You're doing the same thing.' It's almost a challenge to myself to have more time for people that work in that time-base — longer time-base forms.

I suppose Cassils is an artist who works with — it’s very different— but who works with big-picture. They kind of deliberately [are] making spectacle complex. But yeah, Cassils' stuff. Those kinds of people really.

Image: Rachel Mars, FORGE, image credit: JMA Photography

What you’re saying about your interaction with the audience as a performer is so fascinating. When you are performing FORGE, what are you feeling?

Because I am working with quite dangerous stuff, I have to concentrate. I have to do the work. I literally have to do this piece of metal work and I have to do this preparatory work with the metal again and again and again. Then weld it together. There are safety things that I have to make sure I am doing.

And so actually, there comes a point where I can no longer worry about the audience. Like are they having a nice time? Are they bored? Have we done enough? All those questions that you might normally have as an artist, there comes a point where I can't entertain them anymore and I just have to be okay with their experience. And that's just the experience of being an adult, isn't it? Going 'control what you can control. Their shit is their shit.'

But if you are a live artist that's historically used to being in a room facing live humans, you're normally listening meticulously to the response that's coming back and going 'Oh okay, next time if I slow this pause down between this line and this line, I’ll get a bigger laugh,' or 'I need to say this faster because then it will hit harder.' But that's just not what's happening. It's a totally different work. It's a challenge to myself. I set myself [that] challenge, having done all the pre-care work before, and I hope that that's enough.

What has been the most rewarding aspect of FORGE and the changing style of art that you’re working on?

I think it’s the collaboration. I always work in collaboration, but it’s like massively developing a working language and trust with the other collaborators. So lighting, sound, design, production manager, producer, you know? We have designed the experience together. It’s been, yet again, a thing about trust. Like, trust the audience to have their experience and trust people's design experience and artistic nous to do their role with you, together. I think it’s been about that really. It’s been about having trust — not [controlling] to the extent I had historically felt I needed to. But like, just let people do their jobs, they are brilliant at it.

FORGE runs at The Pit, Barbican, from 17 – 20 May 2023 and then touring. From £12. Visit the website for tickets and timeslots: barbican.org.uk.

For further information on Rachel Mars and her artistic journey, please visit:

Website: rachelmars.org

Instagram: @rachelofmars

Twitter: rachelofmars

Facebook: rachelofmars

Word by Sara Bellan

This interview has been edited for grammar and clarity. If you would like to read the unedited transcript, please email hello@flolondon.co.uk.